Therapy Dogs

What is a Therapy Dog?

In the U.S. there is no legal definition of a therapy animal. Common practice defines therapy animals as those animals who visit human healthcare, education, and correctional facilities with their handlers to provide service to the patients/students/residents.

It is unfortunately common for people (including some professionals) to call Emotional Support Animals (ESAs) therapy animals. This is erroneous. The U.S. does have definitions for Emotional Support Animals within various regulations applicable to ESAs.

Who Can Train a Therapy Dog?

As you look at what therapy dog trainers have to offer, consider the value you get from going to a trainer who is experienced with therapy dog work (animal-assisted services). Would you take driving lessons from someone who does not drive? The same principle applies in dog training: what is the benefit of getting therapy dog training from someone who has never done therapy dog work? Yet you can find trainers and training courses provided by people who are unfamiliar with therapy dog work. Be careful.

Ann has been providing animal-assisted interventions in many environments since 1987, both as a volunteer and as paid staff. She understands the field. Ann has education in dog training theory and principles, has worked as a professional dog trainer since 2001, and is a member in good standing with the Association of Professional Dog Trainers. As a result, Ann has the knowledge, experience, and skill to help you and your dog learn what you need to know to be successful in therapy dog work.

Ann no longer provides group classes, but as her schedule permits, she provides consultation or private lessons, including an initial CARAT Assessment to give you feedback about your dog’s fitness for therapy dog work.

Contact Ann to start your journey into therapy dog work. Complete and submit this registration form to begin!

You are a stand-out leader in the field and your contributions are so important to further understanding of the teamwork concept!”

Lindsey F.

My relationship with Ernie, my miniature dachshund, is so much richer for the education you provided. He is not well suited for therapy work but, he is my favorite reason for being! The new awareness I gained through your instruction inspired a desire to be a better companion to my dog and others.”

Carrie P.

What Makes a Good Therapy Dog?

As Patricia McConnell says, “Not all people would make a good therapist; not all dogs make a good therapy dog.” People often ask me whether or not their dog or puppy would make a good therapy dog. In the first place, it is important to emphasize that the dog – or other animal – is only one part of the team. The handler is often more important than the animal in setting the team up for success! Nonetheless, here are some general things to look for in an animal who might enjoy visiting people with his/her handler in a volunteer capacity. (Desired characteristics in a therapy animal who works with a professional therapist can be different.)

- LOVES interacting with strangers. I’m not talking about an animal that is “OK” around or tolerates strangers, but one who seeks out the company of people, perhaps over others of his own species. A therapy dog is genuinely relaxed, confident, and comfortable being touched/handled/cuddled/snuggled/smooshed by strangers (not just family). In other words, a happy therapy animal is forgiving of people who do things that are rude in dog language (or horse language, or cat language, etc.).

- Develops a social and emotional relationship with strangers. In other words, a happy therapy animal interacts with strangers in a manner that helps clients feel like the animal really wants to be with them.

- Is very accepting of and at ease around people acting differently than people do at home. People who are ill, for example, act differently than people who are feeling well. An animal who is worried about people who act differently than what he considers “normal” will not be happy working in animal-assisted interactions.

- Is confident in an environment that is different from home. Visiting environments (healthcare settings, prisons, schools, etc.) contain dynamics that are quite different from home in sounds, sights, smells, energy level, and activity level. A happy therapy animal is confident and feels at home in a variety of environments.

- Has exceptional self-control and focus. Visiting environments are full of distractions. A happy therapy animal is physically calm and content in the midst of both exciting and possibly anxiety-producing distractions. In addition, a therapy animal is able to ignore those distractions and focus on the client.

- Is psychologically sound and mature. It can be challenging to visit people who are physically or mentally ill, incarcerated, in school classrooms, etc. Just like you can feel tired after a day’s work, a therapy animal can feel tired after interacting with strangers. Some animals have a tendency to bring the woes of others home with them. Others let clients’ woes roll off their backs. A happy therapy animal leaves work at work.

- Is physically and emotionally healthy and mature. Adult animals are better able to deal with the challenges of AAI better than baby animals. Some people are overly eager to get their puppies involved in AAI work, yet puppies deserve to have a puppy-hood before they begin working. (There are child labor laws for a reason!) This does not mean that you should delay training until a puppy is an adult. Proper, age-appropriate socialization and training are essential for a well-mannered animal, whether a therapy animal or a companion. Many dogs are most appropriate as a therapy dog when they are 5 years old or older! A happy therapy animal is emotionally resilient and has a healthy, mature immune system.

What an energizing class on Saturday! Thanks for all of your effort and enthusiasm. Glorious and I are practicing and looking forward to The TEST!”

I just wanted to say to you how much this class is giving to Mason and me already. I really find that it is a relaxing, learning time and a great time for me to ‘get in touch with my buddy’ in my very hectic schedule. It is also bringing me some inner peace as I look forward to being able to give of myself and my team to folks that are less fortunate and healthy than we are. It truly is a gift that we have to give.”

Thank you so much for a wonderful therapy dog class! I learned lots and I think Penny & I both are better for it! Thank you, too, for encouraging me to look past my limitations! You’re great!”

Some of those characteristics are largely a matter of personality (or temperament); others can be affected by training. If the animal is physically and emotionally sound, then often the training can follow – if the handler is willing to do so!

I prefer to focus on the positives. At the same time, I have discovered through experience that sometimes people need a list of negatives to really understand a subject. As a result, the following list includes characteristics that are not appropriate for a therapy dog. If your dog has these attributes, please consider a different job for your dog:

- Overly enthusiastic

- Fearful

- Guards resources (toys, food, you, etc.)

- Focuses on you more than on others

- Licks others frequently or drools a lot

- Aggressive

- Health concerns

If you’re considering doing therapy-dog work as a volunteer, complete this Self-Evaluation Questionnaire about you and your dog to see where you stand.

What Makes a Good Handler?

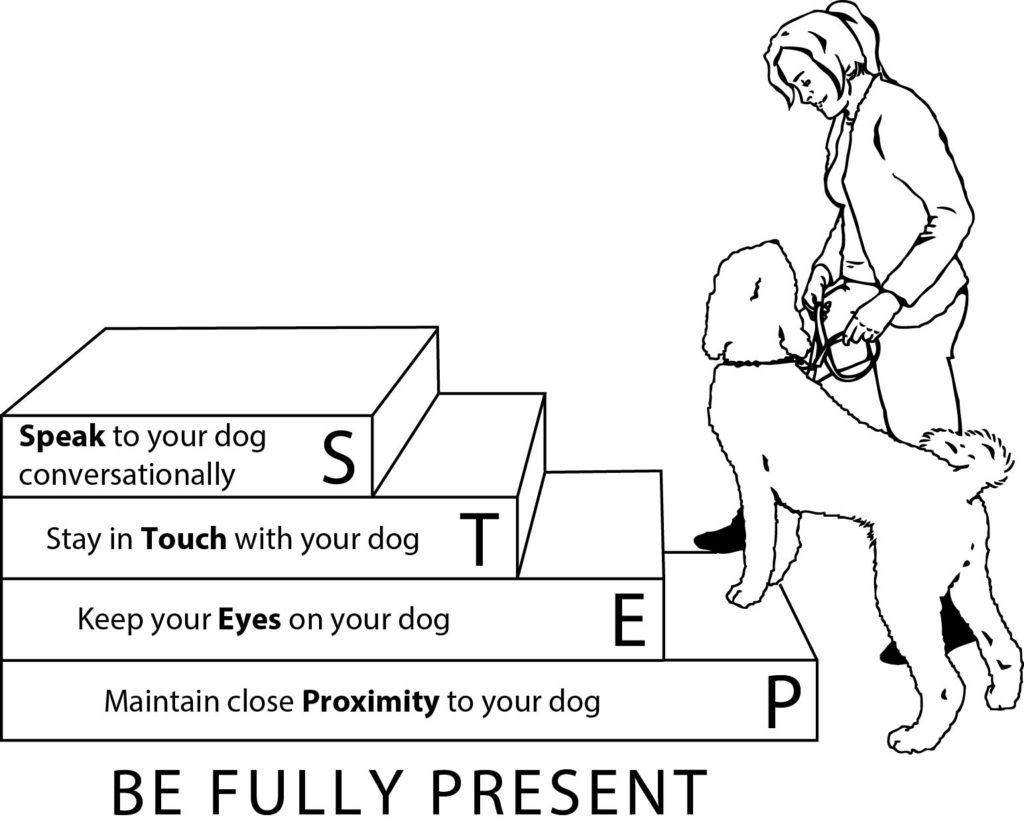

There are several principles of handling that help you be a supportive handler for your dog (or other animal), whether your dog is a therapy dog or your companion. These are called the STEPs of Teamwork®. The following information is excerpted with permission from the book, Teaming with Your Therapy Dog, by Ann Howie (West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University Press, 2015).

Be Fully Present

Being present (centeredness) is the foundation on which all the STEPs are built. Being fully present is about focusing one’s attention, emotions, and senses on participating fully in the here and now.

Maintain Close Proximity

Proximity means the physical distance between you as handler and your therapy dog. Without hovering, close proximity allows you to know more about what is going on with your dog than if you are a distance away. This provides the information you need to support your dog as well as to maximize the effectiveness of the visit for the client. Maintaining close proximity helps your dog feel (literally) that you are there for her. Therapy-dog work is hard! Therapy dogs thrive and feel less stress when their handlers provide adequate support for their work.

Keep Your Eyes on Your Dog

While visiting with your therapy dog, your job is to have your eyes on your dog more than on the client. You certainly must be aware of the client’s needs and preferences as well as what’s going on in the environment and how that might affect your visit with the client. But your focus must be on your dog.

Stay in Touch with Your Dog

When you maintain close proximity to your dog, it is easy to have your hand on your dog. You get a tremendous amount of information from having your hand on your dog. Since it is your job as a therapy dog handler to protect your dog from undue stress, you need to take advantage of every tool at your disposal that helps you perform your job with integrity. Being conscious of your touch and using it in a purposeful way is one such powerful tool.

Speak to Your Dog Conversationally

The way I speak to my dogs is one aspect of behaving with respect and living consciously. The same is true with the “tone” of the hand signals I use. Hand signals given in a conversational tone are most appropriate for working therapy dogs.

The STEPs can be used all together or individually. Because the STEPs are principles, they act as a guide or code of conduct for handlers rather than a law that dictates specific behavior. Not every situation calls for using all STEPs together, but the more you practice teaming with your dog, the more you will find yourself using more of them together. Using one or a few enhances your teamwork, and with practice, everyone gets better.

General Information About Therapy Dog Work

There are three important aspects of competence in volunteer therapy dog work: the handler’s skill, the dog’s manners, and the dog’s personality.

- Handler Skill. There are two primary areas where handlers need skill: handling their animal, and dealing with clients while handling their animal (splitting attention). Animal handling for animal-assisted interventions requires quite different skills than do other dog sports and activities. Some handler behaviors or cues that are appropriate in other settings are quite inappropriate for animal-assisted services. Further, talking and interacting with clients requires one skill set. Talking and interacting with clients while effectively handling a dog requires another skill set. As you can see, the handler must be able to do two things at once! This is where handlers need to be skilled in the STEPs of Teamwork®.

- Dog Manners. The dog must be a very well-mannered dog. In general this means sitting when asked nicely, lying down when asked nicely, walking on a loose leash, leaving something alone when asked nicely, staying in place briefly, and being very, very neutral when meeting another dog. If your dog doesn’t already have these basic skills down pat, then take a refresher obedience course. (Good therapy dog training courses teach you how to apply those skills in a visiting situation; they do not teach you those skills.) Here is where the style of training can have a dramatic effect: Positive, reward-based training methods show up in your dog’s attitude about you and about people being visited. Forcing a dog to visit with people is antithetical to the essence of animal-assisted services. Handlers play a key role in helping therapy dogs be successful with these skills. How the handler does this is the difference between a team that inspires confidence and a team that merely gets by.

- Dog Personality. Visiting dogs must LOVE all kinds of people and still be under control (see manners, above). This means that the dog must be happy (not fearful, stressed, or overly excited by) being around people who look and act differently than how you look and act at home. During an animal-assisted session, your dog might experience rough handling, peculiar gate or movements of people being visited, angry voices, crowds of people all wanting to pet the dog at once, healthcare equipment, and more. Personality is not something that can be taught to a dog. Your dog either has the personality for this work or he doesn’t. Training can help dogs feel more comfortable in situations that might be a little anxiety provoking, but please never insist that a dog love being around people in unusual environments when he really doesn’t love that.

Dogs can also change their minds about therapy dog work after being involved for a while. Have you ever discovered that a job wasn’t quite the right match for you after being in it? The same thing can happen for your dog. We must respect our dog’s choice. At the same time, handlers can learn techniques to help their dogs de-stress and cope with the stresses of working to avoid burnout.

If the STEPs of Teamwork interest you, you’ll find lots more information in Ann’s book, Teaming with Your Therapy Dog.

Contact Ann to get more information about preparing for therapy dog work.

General Clicker Training Information

What is clicker training? You might think that there is a standard answer for that, but in a survey of the top clicker trainers in the U.S. during the summer of 2004, expert Kathy Sdao found that each trainer has his/her own slant on what clicker training is. So here is our definition: Clicker or marker training is a highly effective method of training where we communicate clearly with the dog about what “works” (gets rewarded) and what doesn’t work (gets no reward).

In addition, clicker training focuses on motivating your dog rather than forcing your dog. Most of us want a loving and respectful relationship with our animal companions. If you are uncomfortable with training methods that cause pain to your dog, or force your dog into submission, or end up with a fearful rather than a joyful dog, you will be thrilled with the results you get through clicker training. Clicker training enhances your relationship with your dog without losing performance.

As you might imagine, clicker training does not use force. This method is used to train marine mammals (think Shamu) to do the amazing things they do in shows, and it is pretty hard – no impossible – to force a killer whale to do something. As a result, people with disabilities find that they can train their dogs without having to physically position a dog or force him to do something. Children tend to catch on to this method particularly fast (much to the chagrin of their adults). We believe it is possible for everyone (who wants to) to use clicker training effectively.

One of the most frequent questions we receive is, “Does this mean I have to have a clicker with me all the time?” The answer is, “No.” Some people don’t even use a clicker but instead use another way of communicating with a mark! But during training sessions, it is essential to have a unique way of “marking” specific behaviors in a way that your dog clearly understands. A clicker helps with this. If you are physically unable to use a clicker, your instructor will help you find a way that works for you and your dog. Instructors also teach people how to use a tool they have with them all the time so that when they don’t have their clicker, they can still take advantage of that trainable moment to help their dog learn.

Clicker training is based on scientific principles, not guesswork or trying to figure out what makes a dog do something. (“Is he mad at me?” “Is he trying to get back at me?”) Karen Pryor is a pioneer – and guru – of clicker training in the U.S. Please view her website for excellent information.